Does Haṭha Really Mean Force?

"Forceful Yoga” at an International Yoga Conference in Hong Kong, 2019.

Google “haṭhāyoga” and you are guaranteed to find a definition saying that it means force, or yoga of force. For those of us who have discovered profound tenderness and a way OUT of self-force through Yoga, this seems strange and jarring. Has yoga softened over time? What is the basis of these definitions?

The following interview investigates these questions with Mark Whitwell, a world-renowned yoga teacher of the old school, who for decades has been sharing the tools of body movement and breath and bearing witness to the madness of the yoga industrial complex with compassion. Sometimes seeming to have stepped directly out of a fourteenth-century temple, Mark teaches in the traditional way of transmission between teacher and student through non-hierarchical and sincere mutual friendship and affection.

I interview Mark as someone who does not just hold knowledge of Yoga but embodies it (as you will see if you spend some time with him) about whether “haṭhāyoga” really means “the yoga of force,” as claimed in numerous books and articles. In a world where one study found ‘yoga’ to be more dangerous than all other sports COMBINED, and where ‘yoga’-related injuries are increasing rapidly, do we really want or need a practice whose very name indicates “force?”

The Dirt: Mark, let’s start with the main question: does haṭhāyoga really mean yoga of force?

Mark Whitwell: Well, some have translated and interpreted it that way, and many certainly practice it that way, so maybe we have to say that to them, it does. But I would argue that no, it does not mean that, because if what you are doing is forceful, than it is not yoga.

I have to tell you, I am not an academic. I am not a scholar reading Sanskrit who can look back through the texts and tell you the meanings. I can only speak as a student of my teachers. But I am interested in the findings of those who are doing that scholarly type, and how it aligns with what for all of us should be the main touchstone of truth, which is our own embodied experience. Not our opinions and impressions, because as we know the doors of perception can be pretty shrouded, but something deeper.

The Dirt: So could you give us a quick overview of that research, maybe some leads if people want to dig deeper?

From a study conducted by yogaanatomy.com

Mark Whitwell: Well, for the academics reading this, a place you could start is Jason Birch’s article, The Meaning of Haṭha in Early Haṭhayoga, (Editor’s note: this is available on Academia here.) I found this interesting to hear about what is said in the Tantric and haṭhayoga texts of over a thousand years ago, in some cases.

For starters, it is interesting to me that an academic like Jason Birch finds that all the early references seem to refer to something earlier and lost. So the truth is we don’t have any textual evidence of the earliest roots and uses of the word. It may go way, way back to the time of the Vedas. But I also feel we should be careful not to impose the western academic paradigm of needing textual proof onto what is essentially an Indigenous knowledge system with its own systems of — not belief, that’s dismissive, something deeper — own systems, own ways of understanding reality, that should not be seen as less true than the ‘rational’ academic paradigm. Otherwise we’re just continuing the legacy of colonial cruelty, assuming the western paradigm is superior.

The Dirt: That’s very interesting. Could you give us an example of that?

Mark Whitwell: Take for example Krishnamacharya’s Yoga Rahasya. Krishnamacharya described how this was transmitted to him from his ancestor Nathamuni. This kind of thing is absolutely normal and completely dignified, serious and sincere within the Vedic traditions, the Tibetan traditions, the Yoga traditions… all across that ancient world there is a deep tradition of transmission of teachings beyond time and space. Obviously this gives you a rich tapestry from profound wisdom to total charlatans, and the onus is on the student to sift through that. This kind of thing is dismissed or seen as a quaint anthropological phenomenon by modern academic scholars, starting from the first European Indologists, who want to find out the ‘real’ story according to the known laws of western physics etc. “who actually wrote the piece” — that world actually reveal a lot, the assumption of the superiority or priority of their lens on reality. Charles Eisenstein did an essay, ‘The Feast of Whiteness’ with a good explanation of the problem of imposing a western framework of “but what really happened” onto another culture’s ways of knowing.

The Dirt: I think we could have a whole other conversation about that subject alone. But let’s come back to the findings about what ancient texts say about haṭhayoga. Some people who don’t like the implications of ‘force’ use a translation of haṭha as meaning “sun and moon.” Is there a history of that, or is it a modern new age invention?

Chandra and Surya on a Rajasthani carving

Mark Whitwell: Oh, there is absolutely a deep profund history of that. Ha and ṭha, sun and moon, the union of opposites within and without. Strength receiving, male and female in perfect prior union. This is the essence of the Tantras, and haṭhayoga comes to us from the tantric period, approximately 400–1500 CE.

Many modern books and practitioners have been drawn to the ‘sun and moon’ definition to avoid the distastefulness of ‘force’. I mean people are using force, but they still don’t want it branded as that. But that doesn’t mean it’s a new-age invention. Jason Birch in the same paper finds clear definitions of Yoga as the union of sun and moon in early Haṭha texts such as the Amṛtasiddhi (11th/12th century), and of the syllables ha and ṭha being used to indicate sun and moon, and inhale and exhale in earlier medieval Tantric texts. So this definition is valid, but it’s not ‘the one true definition’ in the older texts to my understanding. We have the word haṭha in use before that definition is first found.

The Dirt: So what did it mean in those earlier contexts? Is it possible to know? (Does it matter?)

Mark Whitwell: Well I think we have to consider what is meant by force. Because there is very much a force we encounter in our yoga, which is the force of life. You know, one aspect of Christopher Tompkins’ scholarly work has been pointing out that there are no references in the tantric literature that he’s studied to a person raising their kundalini, in the sense of a coiled force at the base of the spine. There are references to a coiled force that may act upon you, descending down and then rising up your spine, but we don’t awaken kundalini, we are awakened by it. That sense of I the doer is dissolved. If anyone says to you “I awakened my kundalini” or “I had a kundalini awakening” something has gone very wrong, their identity structure has co-opted an experience of some kind and taken it on as an identity possession. Anyway, force is like this. It is something that acts upon us, something we join up with, something we are, not something “you” as a limited and separate self identity enact upon that poor soft animal of your body. Your yoga is your participation in this force, this power, that you are. Receptivity of it as a nurturing force. Not a manipulation of it, not trying to get to it. Abiding in it. This is how the ancient texts of our tradition speak about yoga, that energy may move forcefully, but not as an act of forceful volition.

Im interested hearing how Jason Birch finds early Haṭha texts using the word “haṭhat” or forcibly, but only toward a movement of energy, not toward the body or into any movement or action. It has a sense of taking the normal downward movement in embodied life and turning it around, but not violently. The implication is “that Haṭhayogic techniques have a forceful effect, rather than requiring forceful effort.” (Birch 2011). Force in the modern sense of pushing these poor old bodies into something that makes them sweat, shake, collapse, strain and sprain is absolutely not there. These are serious devotional practices we are talking about, from the Tantric cultures, one of the lost wonders of the world with their incredible insight that matter was not a degraded shackle for our ethereal souls, but rather just on the spectrum of vibration of the whole cosmos. It’s a similar perspective to the understanding of modern physics that matter is just energy, not solid at all. This was radical, that the body could be a site of liberation, of deity abiding, not just a hindrance to be managed and bullied. The Christian legacy of anti-materiality is deep in the western psychology and has very much shaped the western approach to yoga. We are not that far on from self-flagellation and hair shirts.

The Dirt: So how could we summarise your interpretation of the word haṭha.

Mark Whitwell: I was always taught by my teachers that asana and pranayama must be done carefully and within our breath capabilities, measured by the number of breaths and the breath ratio. So I affirm the academic findings that haṭha can either mean the union of sun and moon — that’s accurate, and poetic and beautiful — or it can mean the great force of life, the energy of life that is moving through us, as us, and which our yoga enables us to receive and participate in. To be devoted to. A great force is moving the planets and oceans, the sun and moon, growing your hair. What is that force? What is the force that grows a seed? That force, that power. We don’t enact that, we recognise and abide in it.

As far as I know, being shown the academic researching of Jason Birch and Christopher Tompkins and others, “the word haṭha is never used in Haṭha texts to refer to violent means or forceful effort.” (Birch 2011). That matches my experience with Krishnamacharya and Desikachar, and their students. All emphasise that the key qualities to master āsana were comfort, ease, and stability. Never force.

The Dirt: Could the association of yoga with the word force be to do with the association with tapasya, with ascetics?

T. Krishnamacharya with his wife Namagiriamma, elder sister of the distinctly forceful BKS Iyengar.

Mark Whitwell: Yes, there has been great confusion in the last 500 years between ascetics and yogis. You might like to refer to the excellent article by my dear friend Domagoj Orlić, ‘Why Yoga is Neither Physical Gymnastics nor Spiritual Gymnastics.’ Yoga became associated with obscene acts of self-torture, holding one’s arm in the air for years and years, a metal grate around one’s neck, and such extremes. Yet these extreme practices are not there in the Tantras, the Shastras, the Haṭha texts. They are not yoga. Mortification of the flesh is the opposite to realising the intrinsic union of the Source and the Seen. It was the early Europeans coming to India and trying to understand what they saw that really popularised an idea of yoga as force, as self-violence. Perhaps reflecting the internalised violence of their own culture. A kind of projection that Patañjali’s Yoga Sutras warns us about. And getting confused with the fakirs and ascetics, and seeing it all as a suspicious kind of witchcraft. India internalised all of that British projection and judgement. By the time Krishnamacharya was teaching, yoga was not seen as a high or holy calling. This was a man with the equivalent of six or seven PhDs, yet he was teaching yoga, as a very serious undertaking, in a time when it was not taken seriously at all. He would do some kinds of “feats” at the Maharaj’s request, such as stopping his pulse for doctors, that kind of thing. But he refused to teach this to his son when he begged him. He said it was just to get attention for yoga, to get the ball rolling, so to speak.

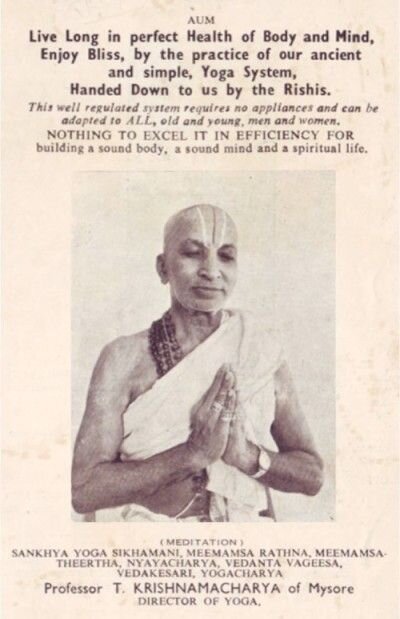

A poster for Krishnamacharya’s teaching at the Mysore Palace under the patronage of the Maharaj. Note the emphasis on not just body but also mind, spirit and life, the emphasis on adapting to the individual, and how it “requires no appliances” ie no exercise equipment or ropes etc.

Krishnamacharya’s many qualifications are listed beneath the image.

The Dirt: So there was/is also a confusion between ascetiscism and yoga within India as well?

Mark Whitwell: Yes. It’s something Desikachar would often clarify. Krishnamacharya really stood apart from any of the traditions based on anti-body philosophies, dualistic transcendent schools that saw the body as a bag of rotting flesh, a meatsack, that needed to be bullied and purified and ideally gotten rid of altogether ASAP. That kind of school has denigrated āsana and pranayama the way they denigrate the body itself. Krishnamacharya’s lineage came from the 10th century Ramanujacharya, who had declared that yoga was the means that the two became one, and that householders and ordinary people could and should practice this. He wasn’t from a monastic, man-alone type tradition. Even his guru in the Himalayas, Ramamohan Brahmachari, lived there with his wife and children, in his accounts. The son would accompany Krishnamacharya back to Simla for several months each year.

So Krishnamacharya really represented the coming-together of these great traditions of Vedanta and Tantra, which belong together. They are branches from the same great tree and are now back together.

The Dirt: And finally, could you tell us what you have observed in terms of the impact of this misunderstanding on people’s yoga, and how to correct that.

Mark Whitwell: Thank you. Thanks for caring about all the people out there, sweating away and struggling and getting injured. The idea that the body, that the earth, that the feminine is less, something to be conquered and controlled, has done great harm. It is the basis of centuries of patriarchal culture. And that cultural split, between some sense of essence within, and a dead materiality without, has enabled humanity to use and abuse its Mother, the body of Nature, and our own bodies are part of that body. So the conditioning towards a forcefulness towards embodiment runs very deep.

This is the same psychology in the earlier Indologists translating haṭha as “yoga of force” and in the bullies who rose to prominence in the yoga world. And then the same psychology in the western students, who had been conditioned to control themselves, restrain the body, who were beaten at school, who thought a good teacher hit you with a stick to help you get it right… who were beaten by their parents… this is the western mind, the modern mind, the cultural framework now being investigated as “whiteness,” but I don’t think that is accurate enough, as it is not intrinsically tied to skin colour. Basically it is deeply in us to bully and force the body, and yoga is meant to be our way OUT of that, into reverence and ease. Yet it has been popularized as mere duplication of the same old hegemonic patterns of abuse.

Your body is tired. It’s been forced into so many things it didn’t want to do. Deprived of sleep, hungry or over-filled with comfort food, too much or too little, plucked and poisoned, whipped along in jobs it hated, forced to work inhuman hours just to survive, squashed into uniforms and cubicles, numb to the ordinary pleasures of a free-born life. Yoga is the freeing of our bodies from all of this, the freedom to be that soft animal, that embodiment of love, that piece of wild mother nature. Of course this demands change in our social circumstances, where a few hoard wealth, while billions search for their next meal. Yoga is emancipatory in that it sensitises the body to these things, creates the demand for change. Our yoga is careful, precise, different for each unique embodiment. Please, don’t throw yourself around in the circus gymnastics they’re calling yoga. It’s just simply not. It’s all made up. There is no precedent for this kind of insane forcefulness, this self-violence. Step out of it all and be free, live your life in the garden.

Strength AND receptivity… the form of all life.